Arek Socha

creative salon selects

Graffiti - Visual Art or Visual Pollution?

Last summer Banksy indulged in his 'Great British staycation'. We looked at the rise of street art during lockdown and asked people to name their favourite graffiti

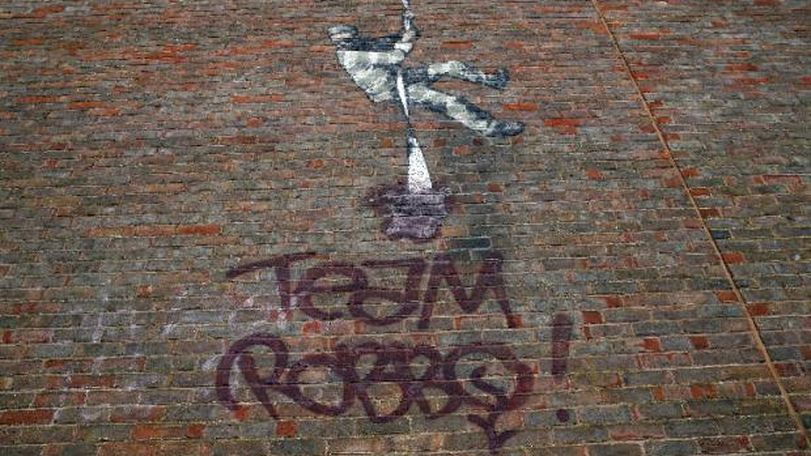

That’s partly because sneaking around with spray cans became less risky on streets that were suddenly deserted but there’s also no doubt that street art afforded a much-needed form of creative expression when people were bored and frustrated, and has entered a higher level in the public consciousness due to new found media interest in the art form. There was ample coverage, for instance, of the ongoing feud between Banksy and supporters of the deceased graffiti artist King Robbo, which resulted in the “defacement” of a recent mural on a wall of Reading prison.

Brands of all sorts have been quick to jump on the street art bandwagon. Not always finding favour with audiences. After success with some edgy outdoor campaigns in the UK, London-based oat milk brand Minor Figures faced a serious backlash in the US when it pasted its own street art-inspired campaign over the work of local artists in Philadelphia. One of them, Kid Hazo, calling out the brand with his own art using the line “MAJOR FAILURES. CLOWN M*LK”.

For the most part, though, creatives feel energised by the expressions of creativity they’ve seen out on the street – even though they’ve often had to witness these second-hand through social media rather than in person due to lockdown.

Matteo Alabiso, senior designer at Droga5 London, was born and bred in Milan, experiencing at first-hand its vibrant graffiti scene, before finishing high school and moving to the UK, where he graduated in graphic communication and moved into advertising. He says: “I’ve heard the rise of public conversation. Lockdown meant that people were really deprived of the public space and I guess graffiti, but also paintings of hands and rainbows in windows, were all signs of self-expression and having a conversation with the public in a very open way.”

Others agree. Serhan Asim, a creative at Lucky Generals, says: “I’ve felt like street art has always been around but is getting more and more popular. The perception of it is also changing thanks to platforms like Instagram. But perhaps people have become more connected with their communities during lockdown and have started to realise all the amazing bits of art that exist within them.”

Sophie Cullinane, creative director at Gravity Road, lives in Dalston so has been able to witness the latest street art directly: “It’s been great for street artists, there are fewer people on the streets so more opportunity to start tagging and bombing, and more shop shutters to start creating on. So, at a practical level, this has opened opportunities for graffiti writers. In Dalston there’s some amazing work at the moment, it feels really vibrant again and has added to a real sense of community, and an energy to the graffiti and street art scene that wasn’t there a couple of years ago.”

Creative people within advertising have long been influenced by a vast array of street art. But what inspires them more specifically? Matteo Alabiso at Droga5 cites graffiti artist Blu as a formative early influence: “The first piece of work I saw from him was at the PAC museum in Milan, I must have been 14 or 15. He drew this enormous mountain of white powder and different people diving into it. It was a bit shocking but I found it amazing with the scale he adopts in his work.”

Alabiso’s favourite work from Blu, though, is ‘Muto’, a film that mixes stock frame technology with graffiti: “What I love is that he draws something, paints over it, and creates a narrative using space. It starts from the street and expands. Frame-by-frame technology is dated but the way he repurposed it with street art I found very fascinating.”

In terms of more recent work, Alabiso is drawn to the art of Felipo Pantone, the Argentinian-Spanish artist who started out in graffiti aged 12. Alabiso says: “Despite being a street artist, he has this screen quality to his work. The way he renders his pieces of work, captures a digital feel in a natural, physical space, is very fascinating. At the same time I also love how he’ll take the façade of a building and put a big panel on top to break that convention.”

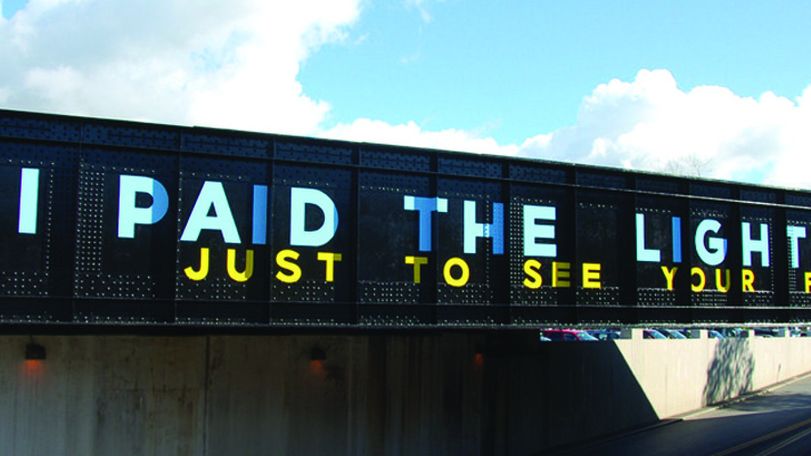

Another creative drawn to large scale street art is Stu Royall, associate creative director at BBH London. He mentions the murals created by Stephen Powers, the Philadelphia-born artist, as an influence: “He uses really big words on big buildings that has a real wit and warmth to it,” says Royall. “He did a project in Philadelphia that was 50 murals around the city, which could all be viewed from a high line train. It’s a love letter to the city, using almost cheesy pick-up lines, but there’s something about the sheer scale and commitment involved in hand painting these enormous messages around the city that elevates it to being something quite romantic and moving. And it’s a bit joyous, as they add real value to the community.”

Royall adds of Powers: “If he wanted, he’d be a very good advertising creative. The cadence in a lot of the lines feel like advertising slogans. I like great outdoor advertising, which brings joy and creates value and respects its audience and surroundings. Unfortunately, most of it is just visual pollution but the really good stuff can aspire to that level.”

Cullinane, at Gravity Road, admits her tastes are more “on the criminal damage end of the spectrum” including Tox (Daniel Halpin), but she’s also enthusiastic about Teach, and Gary Stranger and Pref – “proper graffiti writers who happen to do street art.”

Nick Hearne, also a creative director at Gravity Road, and who worked on the Google StreetArt initiative for its Cultural Institute, which launched back in 2014, says his tastes have evolved: “I used to like the rough stuff but love everyone who has crossed over to art now. For example, a friend Donal Sturt is a graffiti artist making beautiful pieces of art. People like him and Cyrcle in America, and MadC, who I worked with on the Google StreetArt work - they come from painting these walls but now are right in the establishment.”

Serhan Asim at Lucky Generals says that Keith Haring was an early inspiration (“I’ve always been really drawn to the way he’d juxtapose his simple illustrative style with hugely powerful statements”) but he’s also fired-up by the art on the streets around him: “One project that always stuck out in my head was by artist Ben Wilson, who used to go around London painting dried bits of chewing gum, which were stuck to the pavement. I loved the idea that someone had gone around London leaving these colourful and peculiar ‘Easter-eggs’ for people to unexpectedly stumble on.”

And he retains a fondness for the street art in Tottenham where he grew up: “For years I’d take the bus past the giant snail mural located next to Seven Sisters. Anyone who’s grown up nearby has a soft spot for it.”

In terms of influence and connection to advertising, Cullinane says there are similarities: “We trade in immediacy in advertising so that kind of immediate emotional response is something that you try and achieve when you’re creating ads or content.”

Royall has also seen street art make an impact on advertising creativity: “Advertising has borrowed from street art for a while now. There was a craze for every car ad in the early noughties to feature some sort of animated graffiti. But it felt watered down. Where it’s slightly more interesting is the more punk DIY ethos, where there’s some sort of guerrilla installation. Where it’s less about paintings on walls than sculptures left in the middle of the city, something that feels a little more anarchic than a watered-down pastiche. “

He says that his own work for Burger King at BBH was directly influenced in this way when the brand’s ‘Election Whopper Bus’ was parked directly in front of the Houses of Parliament. Royall describes this as a “a proper guerrilla stunt, that thumbed its nose at the establishment. Not many big brands have the confidence to make political statements like that.”

Droga5’s Alabiso started experimenting himself in graffiti aged 14 or so: “Street art was embedded in me very young, I think it was difficult for me to not be part of it because I went to an artistic high school and everyone in that school was part of the graffiti scene but, at the same time, I learned very quickly how there is a big difference between adding value to the streets and detracting value.”

Alabiso says that street art remains a big influence, especially due to his passion for typography, which grew in part out of his attempts to combat severe dyslexia: “When it comes to graffiti the beauty is the fine line between pushing the basic shape of a letter to the max, giving it a sense of movement and dynamism dictated by what you do with your arms, it feels organic. And that for me, when it comes to creating custom pieces of typography and titles in my various projects, has really showed.”

He says this was especially the case for his work at Droga5 on the branding around the launch of the Coal Drops Yard retail site in London: “It had a graffiti feel to it because there was nothing recycled twice, it combined different pieces next to each other and assembled them as a puzzle.”

Alabiso believes there’s room for even greater street art influence on advertising: “The beauty of graffiti and the untapped potential for advertising is that it’s a vehicle seen in a different way. If you approach a billboard, you’ll automatically think that you’re about to receive a consumer message but if you do a similar thing with graffiti it doesn’t feel like a billboard, it opens up a conversation. You’re using your money to add value to the street rather than land a message.”

More importantly, perhaps, the vast array of talent in the street art scene and the diverse types of creativity on show, provides a possible way to help advertising become more inclusive and creatively compelling. Gravity Road’s Nick Hearne concludes: “It’s important to have those people with a rebellious streak within advertising because you need people to change attitudes and bring inclusivity.”