Fifty Years Of Planning And Why Stephen King Still Matters

It's half a Century since King published his Planning Guide but its principles are as vital as ever

08 April 2024

Fifty years is a long time; the world has changed - our industry has changed - in ways and at a speed that would have been hard to fathom in 1974.

In some ways Stephen King's Planning Guide is a relic from the past. Typed out - on a typewriter, copied mostly likely on an early Xerox machine, it became an industry touchstone for the developing discipline of account planning. That it's still beloved and used by planners five decades later is testament to King's groundbreaking but eminently sensible insight, his accessible style, and the type of people that have found their professional home in the world of planning.

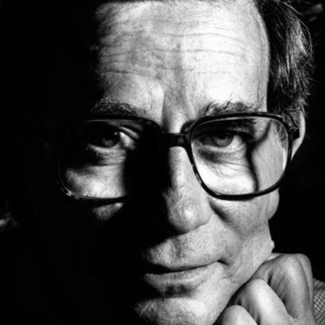

King spent most of his career at J Walter Thompson (one of the mighty advertising networks of old, whose DNA - or what's left of it - now resides in WPP's VML). A rigorous yet unpretentious thinker, he's sometimes called the Godfather of planning, and was certainly one of the pioneers of the discipline and its ability to unlock the power of brands. Writing his obituary in Campaign in 2006 his former colleague Jeremy Bullmore wrote of King: "He never showed off, never used jargon (unless to parody it) and could spot - with gusts of contagious delight - bullshit at a hundred paces. His influence can be detected throughout the world but goes largely unattributed. Only that fortunate 7.34 per cent of us know just what the man achieved and how much we owe him."

That 7.34 per cent certainly includes some of the leading strategists working in advertising today. Here they discuss King's legacy, why he still matters and what the future holds for planning.

Ben Worden, CSO, VML

In my experience the greatest gifts can appear insignificant at first.

And so it is with Stephen King’s Planning Cycle - the simple diagram that sits at the heart of the JWT Planning Guide - first published in 1974.

A lot has changed in the last five decades, but the Planning Cycle remains a gift to strategists everywhere.

No proprietary methodology.

No ridiculous buzzwordy name™.

No jargon.

No complicated acronyms.

No requirement to have a certified agile scrummaster present in the room before you attempt to use it.

Just five common sense questions that have helped build brilliant, creative, effective strategy for almost five decades. The beautiful thing is, those same five questions are as relevant to the work we do today as they were back in 1974. There are three reasons for this:

1. Great strategy is about problem solving. The Planning Cycle forces you to stare hard at the problem, and really understand what’s going wrong and why.

2. Great strategy is about sacrifice. The Planning Cycle demands that you be selective. In this age of information overload, it’s all too easy to include ‘stuff you found’ even if it doesn’t have clear a role to play in solving the problem at hand.

3. Great strategy is about imagination. The Planning Cycle encourages you to define the problem precisely, but think about the solution in a way that’s expansive, challenging and different.

The other amazing thing about the Planning Cycle is that it never produces the same result twice. Every time you use it, the inputs are different, the circumstances are different, and the outcomes are different. The framework never changes, but it continues to produce fresh and inspiring strategy that solves real problems of every kind.

If I was asked to write the 2024 edition of the Planning Guide, I’d be hard pushed to start anywhere better than the original Planning Cycle. But where else might I turn to for inspiration? Here are three things that I couldn’t live without:

- How not to Plan, by Sarah Carter and Les Binet. Inspirational and hilarious in equal measure. Never underestimate the amount that can be learned from getting it wrong!

- The combined works of Les Binet, Peter Field, Tom Roach & Dr Grace Kite. The effectiveness landscape is in constant flux, but these four legends of the game somehow know how to shine a light on which changes matter, and which ones will make a difference to the bottom line for clients.

- How to Make the World Add Up, by Tim Harford. This is a numbers game. Make sure you know the difference between good numbers and bad numbers.

Josh Bullmore, CSO, Leo Burnett

Stephen King’s Planning Guide introduced so many timeless tools to our trade, not least the Planning Cycle, which remains one of the most useful ways to think about solving any kind of problem, in advertising or beyond.

For me though, the guide serves as a reminder that the value of planning lies first and foremost in its partnership with creative people. As King puts it, planning “must actively stimulate imagination and creativity”.

I am distantly related to Stephen King’s creative partner, my Bullmore namesake Jeremy.

To my regret Jeremy and I only ever had one lengthy chat. Amongst the wisdom and anecdotes he shared were fascinating stories of the invention of planning.

Prior to King’s emergence, planning’s forbears were the research department: so unglamorously portrayed in the Mad Men series as tolerated but peripheral.

Jeremy, as JWT’s creative director, enthusiastically embraced Stephen as a partner and they enjoyed a groundbreaking working relationship.

The guide is, in part, Stephen’s effort to enable others to replicate that relationship.

As we look ahead, I believe that same planning-creative partnership will remain fundamental to the industry’s future.

At the Account Planning Group (the industry body for planners of which I’m a committee member) we are keenly exploring what lies ahead for our craft.

Martin Beverley, APG Chair, recently summed it up beautifully in these pages: “if the future of planning can bring together old-fashioned principles with new-fashioned technology, then we won’t go far wrong.”

For my money, Stephen King’s planning guide remains the cornerstone of those old-fashioned principles.

Jo Arden, CSO, Ogilvy UK

The most remarkable thing about King’s Planning Guide is how well, even fifty years on, it sums up the job done well. Whether they know it or not, most good planners follow the planning cycle in the day to day of the job. Perhaps the perennial power of this guide lies in its simplicity: it sets out in logical steps, how to create strategy magic.

The last twenty years have seen a fine-slicing of strategy. We have more types of strategists and planners than ever before. Specialisms are important, we have more at Ogilvy UK than most agencies and we are especially powerful when we work together. But any specialism must be built on core skills which are no different from one discipline to the next. Give King’s guide to anyone working here and they would see their role reflected.

Planning roles will evolve as new inputs, sources and technologies continue to emerge and can be applied through the be used throughout the cycle to make the work richer, and the practice more efficient. Strategy leaders can help teams by coaching them on how to keep the rigour whilst making pragmatic changes to their process. The guide was created when planning (and the work of marketers and agencies generally) was done on longer timeframes and with less complexity. The ship has sailed on slowing things down, but good and fast are not mutually exclusive – discipline is key and that’s what King’s guide gives.

One area of the guide which is fascinating is research. King’s approach is to use it to ‘disprove hypothesis’, something which we rarely have the luxury to do today. We now have much more convincing ways of using research with positive intention – to get a gauge on not only whether an approach will work, but how well it will work too. Whilst no approach is infallible, we can be more confident than we were fifty years ago. But testing with an intention to welcome failure has fallen out of favour. With the exception of pitching, where the budgets are our own and the results less exposing, a bad debrief is generally bad news. Time is shorter, stakes are higher and our collective capacity for criticism diminished. Whilst AB testing in live environments is pretty common now, it’s used to fine tune more than with the unguarded curiosity King’s type of testing encouraged.

We have a wealth of planning resource today – notably the APG’s brilliant 'How not to plan’ by Sarah Carter and Les Binet – and we should be always open-minded to new thinking. But the fundamentals of planning, as set out in the guide don’t radically change. Planning is about understanding people and solving problems – the rest is all approach.

Emily Lewis-Keane, head of planning, Saatchi & Saatchi

In an act of selfless romance, I read this out loud to my husband as a fun audiobook alternative on a long drive to France this Easter weekend. And, forgive the heresy, but my god was it a slog.

As I waded through its 37 pages, what struck me most - 50 years since its publication and 15 since I first read it myself – is that its sheer intellectual density highlights a significant shift in the seriousness and confidence with which planning presents itself.

King is academic in his approach to planning, crystal clear in how he thinks things work, and why, and how we should get there.

He has no fear in acknowledging, very rationally, the irrationality of the creative process. He recognises that it is messy and circular, full of random collisions of stimulus. But that doesn’t make it any less serious, it makes it akin to the processes of the greatest scientific discoveries.

The great modern planner is a provocative thinker and a verbal magician. Yet while the best of us might be pretty enthralling, I think many CMOs would level at us the same loving put down that Logan Roy levelled at his own children, “I love you, but you’re not serious people”.

Because somewhere along the way we lost the confidence to explain and advocate for creativity, and we’ve let the Kantars, System1s and Ehrenberg Bass’s of the world fill the gap we’ve left – the gap that that explains what works, and how, and (most worryingly for us) what you need to do to create it.

When the modern CMO has a serious concern, it’s not us she’s turning to. The serious, grown-up work has been absorbed by pre-testers, marketing scientists and consultancies.

While King talks about the planning process as a cycle of developing and then trying to disprove hypotheses, we have fallen into the trap of confirmation bias - we believe the dogma, limit the inputs accordingly and then set out to prove them right – creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of increasing mediocrity.

We need to get serious again about how the creative process actually works and why, to take back control and challenge the doctrine that’s filled its place. To liken ourselves to scientists on the quest of discovery again. King has reminded me that it’s imperative planners reclaim our status as serious people.

Michael Lee, CSO, VCCP

I loved revisiting this iconic document! In fact I would heartily encourage everyone in our profession of the value of putting some time aside to read it. What's remarkable about it is that you'd be hard pressed to find anything in a 50-year-old document on planning best practice that doesn't have some value and benefit to the day to day job of planning today.

What you also can't avoid is the feeling that the planner of the 1970s had a hell of a lot more time than today to properly interrogate the brief from all the angles that King recommends, and to muse, hypothesise and investigate with rigour before being expected to declare your strategic hand.

If you were to try to adapt it, I think the biggest two changes would be the expansion of King's brand references beyond the slower-moving FMCG and physical goods world, into the much faster moving world of digital services and tech brands. Secondly, I'd love to know what he would have made of the world of digital and social media and the shift to performance marketing and its impact on how effectiveness is evaluated and creative is developed. And obviously there's the name itself - planning. Having been in endless navel gazing sessions about whether we're better off being called planners or strategists, I wonder if he'd regret the can of worms he's created!

Gen Kobayashi, CSO UK and EMEA, Weber Shandwick

The marketing industry is in a perpetual state of flux. Disruption is the norm. We’re forever looking over the horizon wondering how we’re going to tackle the next monumental change in how the industry operates. From AI to the talent drain, we’re having to shift not just WHAT we do for clients but HOW we do it for them. However, I would argue the one thing that doesn’t change is that we’re in the business of understanding what motivates human beings. Marketing at its core is a people-orientated endeavour.

And this is why Stephen King’s Planning Guide from 1974 is just as relevant today as it was 50 years ago. King lays out some fundamental truths as to how best leverage communications in a way to motivate people to do something. From being clear about WHO you are speaking to (in his words “The Target Group”) to be clear about what the “desired response” to communications should be, King speaks to “indirect vs direct response”. Being clear about what you want people to “feel” about a brand.

These questions remain just as fundamental to brand strategy today as they did 50 years ago because the context of marketing may continue to change but human behaviour remains constant.