The Art of Warts and All

Why making a virtue of a brand's perceived shortcomings can be a good advertising strategy

03 November 2021

The Japanese art of Kintsugi is the concept of highlighting imperfections, visualising amends as an additive or even as areas to celebrate or focus on. It is a beautiful and almost 500-year-old art that reminds us that life isn’t perfect and that that isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

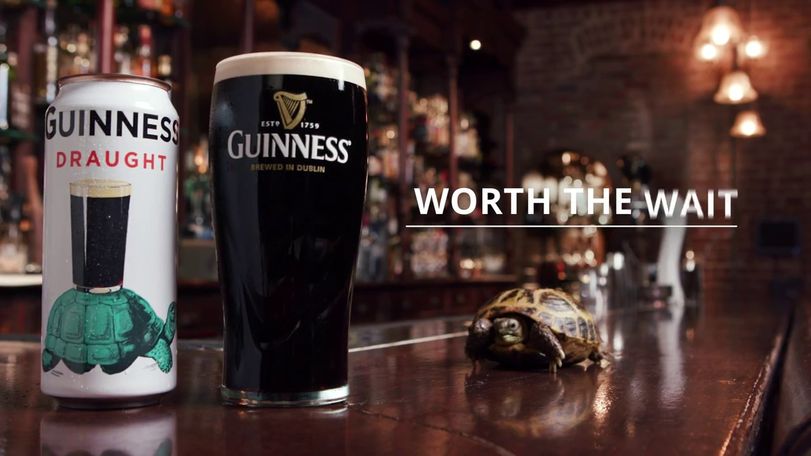

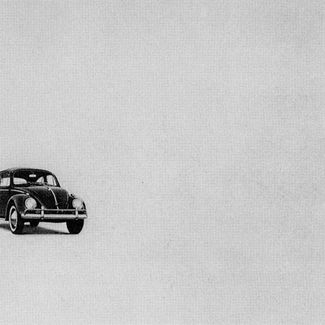

Whether or not they knew it, many brands have been practising the art of Kintsugi for years: take Guinness’ iconic ‘Worth the wait’ campaigns – a slogan coined by Abbott Mead Vickers BBDO in the ‘90s - that stressed that the patience of waiting for a glass of Guinness was a virtue rather than a pain. Or even as far back as the ‘50s, when brands such as VW flaunted offering a tiny car in an age of supersized motors and spinning its size as uniquely positive in ‘Think Small’ by DDB.

Some of the most memorable campaigns have emerged from this art of self-reflection and honesty, but why is it so effective? And which brands can pull it off? The art of ‘warts and all’ in advertising may seem counterintuitive — after all, consumers more often than not prefer better (or more efficiently delivered) products over ones that may appear to have shortcomings — but if placed rightly, then it has been proven to be immensely effective.

More recently than ‘Think Small’, Doc Martens ‘How to Break In' by Breaks continued in this tradition in advertising, capitalising on the one thing everyone knows about Doc Martens: they hurt to break in.

It is this element of acceptance of your product that is key to what makes these campaigns so good. The campaign itself features a medley of methods consumers had proposed online. From stuffing their boots with baked beans to freezing them, the spot bombards the viewer with shot after shot of bonkers solutions to this problem.

“If we had pitched the idea, the client would never have gone for it,” says Isabel Mickleburgh, creative strategist on the project, “it was a bit of a wildcard, but the idea came from a brand truth that was already clearly out there: you can’t have one without the other, and that is inherently a good thing”, Ritz adds: “It’s a testament to the sales data. Consumers were typing in this question all the time onto the DM’s website, so this wasn’t a problem worth denying but embracing.”

That’s often an overlooked point when marketing a product: fundamentally it is what those who actually have experience with it say it is, not what a marketer or advertiser might wish it or pretend it to be.

Take Carlberg’s ‘Probably Not the Best Beer in the World’ campaign by Fold7, which took hyper-critical posts lambasting the product as a segue to announce changing of its ingredients. Or ‘Ain’t No Small Fry’, a campaign for KFC by Mother, which did a very similar thing when relaunching its fries. In it, the fried chicken chain announced that it was getting new fries, a decision probably not so far disconnected from the fact that its previous fries were being constantly flayed on social media.

In fact, a third of all complaints KFC ever received were about its fries. Even so, when the chain relaunched its “tastier, chunkier fry” — which tested well in research — the new chips were underperforming in taste testings due to loyal fans of the old chips being resistant to change.

To change perceptions, Mother realised that just talking about how good these new fries were wouldn’t work, instead it needed to acknowledge the problems with the old fries in order for the new chips to be seen as the answer to a problem, bringing these loyal fans on the journey alongside the brand in the process.

The result of broadcasting the hate of its old fries across social, in traditional media and out of home, on a budget of just £230,000 was 13.9 million impressions across social media. Alongside that, taste scores improved across every measure, while KFC’s scores for relevance were up 3 per cent, generosity 4 per cent, quality food raised by 1 per cent and trustworthiness also improved 4 per cent.

As anyone in branding will know, trust is everything. Brands originated from ‘Trustmarks’, symbols of trust after all, which effectively guaranteed consistency in service. However, as much as a product must be up to scratch in order to facilitate trust, showing honesty, as all of these campaigns do, will do that too.

Dave Monk, executive creative director at Publicis.Poke, agrees that honesty is the best policy: “The age of the advertising conceit is over. Honesty is a currency more valued than ever. Any brand that’s self-aware enough to know what they’re good or bad at and then put that front and centre should be carried aloft on a caravan. The world will turn your brand off at the flick of a thumb, especially if there’s a whiff of bullshit.”

Indeed, as Michael Pring, acting chief executive of AMV BBDO, says: “Knowing your brand’s truth is as important as knowing its purpose. It’s a source of credibility in a world where consumers are looking for authenticity and integrity.” With a brand like Guinness, he says, it’s more than just that: “Guinness is a case in point – the bold spirit of Arthur Guinness, the magic of the liquid and the optimistic view on life that is in the brand’s DNA has consistently shone through in the work.”

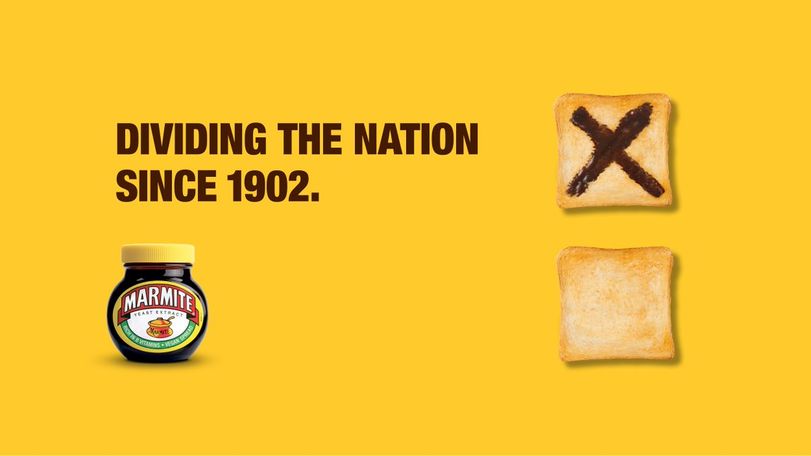

So can any brand spin a true negative into a positive? Martin Beverley, chief strategy officer at adam&eveDDB, says: “The negative needs to be distinct. Marmite is a good case in point, you either love it or you hate it, but the thing is only about 10 per cent of people haven’t actually tried it, so almost everyone knows if they love it or hate it already.” For this to work then, Beverly adds, “the brand has to have a perception to play off”.

In social psychology, the pratfall effect is the tendency for interpersonal appeal to change after an individual makes a mistake, depending on the individual's perceived competence. When we see brands make mistakes, or make fun of the product they are attempting to sell us, it engages with us on a psychological level.

“The effect was discovered in the ‘60s,” Beverley says — referencing an experiment by social psychologist Elliot Aronson in 1966 — “where job applicants who spilt coffee on themselves were more likely to get the job than applicants who did not.” In short, the conclusion of the research is that people perceived to be competent tend to be more likeable after making mistakes.

This being the case, it makes sense that campaigns that play on this psychology will also help make brands likeable. “It brings you closer to the individual,” says Beverley. “It humanises them. I heard that Allen Brady & Marsh used to put little mistakes into their pitches to make them appear more likeable for the same reason. But obviously, if you keep fucking up, it is no longer charming”.

Ultimately, the art of warts and all is a multifaceted one. It requires a product to be known, a brand to be knowing of its consumers and those working for it to be brave enough to be brutally honest about what it is they are selling.

As Dave Monk concludes: “It’s about running towards what your competition usually runs away from, because that is where you’ll find yourself asking deeper and sharper questions, and sharper questions shape great work. Maybe if we all started being more honest around the negative stuff, the industry might just end up somewhere way more positive.”

And hopefully with less people stuffing beans into their Doc Martens.