No Ham, No Fowl: How to advertise a brand without showing the product

Elliot Leavy researches how to advertise products without showing them, in light of next year’s HFSS regulation

07 October 2021

“Britannia, that unfortunate female, is always before me, like a trussed fowl: skewered through and through with office-pens, and bound hand and foot with red tape,” wrote Charles Dicken’s in David Copperfield back in 1850. Following 18 months of hyper-regulation due to Covid, one wonders what the writer would have thought about much of life in Blighty today.

Because over 170 years later, it seems that our love for red tape hasn’t stalled in the slightest. Next year’s HFSS regulation (advertising restrictions placed on products that are high in fat, salt or sugar) likely means that many advertisers are unlikely to be allowed to show any fowl — trussed or otherwise — at all.

This raises a quirky question for many brands: how do you advertise a product without showing it?

The new rules to come in effect next year will ban TV ads for products deemed to be HFSS before the 9pm watershed. Paid-for ads on sites including Facebook and Google by big brands will also be banned.

What makes this interesting is that brand-only advertising online and on TV will continue to be allowed, so companies associated with 'junk food' products can market themselves as long as those products that fall foul of the rules do not appear.

But what is McDonald’s without a Big Mac? KFC without the fried chicken? It seems we are about to find out, as HFSS regulation will force brands to ask what they are besides what they sell.

Ben Mooge, chief creative officer at Publicis Groupe, has come up with the brief for the Publicis Student Workshop that asks applicants to answer this very question.

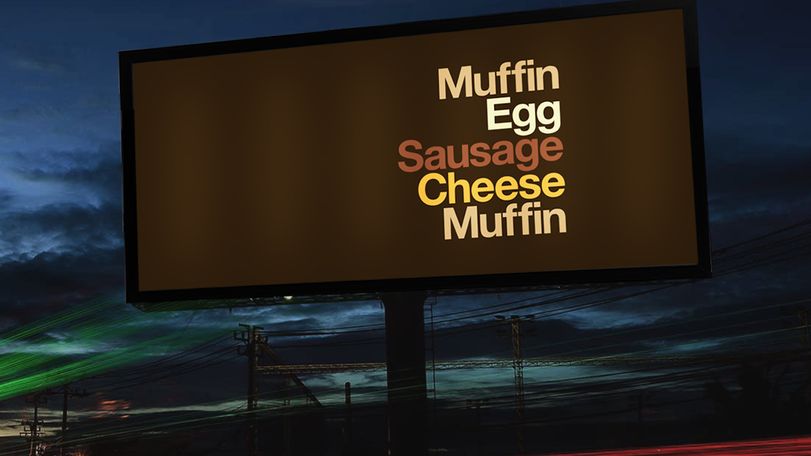

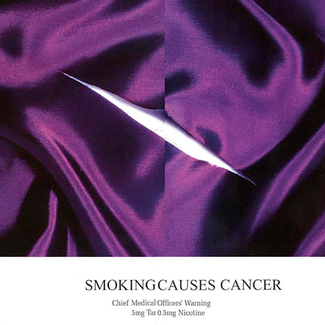

In the brief, Paul Arden’s iconic ‘Slash’ ad from Saatchi & Saatchi for Silk Cut (1990) [main image], and Fallon’s similarly famous — and purple — ‘Gorilla’ for Cadbury Dairy Milk (2007) [above] are mentioned.

But what was it that made them so great at showing what the brand was about without showing what it was they were selling?

“With ‘Slash’,” explains Mooge, “it was all about playing on the name, the allure of the product — it was everything that a smoking cowboy wasn’t. With ‘Gorilla’, it was about dramatising the feeling of the product. It was based on colour cues and built on the ubiquitous nature of the brand in the nation’s consciousness.”

When it comes to advertising a brand without a product, then, having a strong brand to play with goes a long way.

As Hamish Cameron, strategy director at Leo Burnett London, says: “This type of advertising works most effectively when you have absolute confidence in your product and people’s perceptions of it.

"With our 'Iconic Stacks' campaign [above] we knew that just the act of listing the ingredients to McDonald’s most famous products would instantly put them in the viewer's mind’s eye.”

But what if the brand isn’t as ubiquitous as McDonald's? “Obviously, it’s a bit harder to do,” says Cameron, “which is why it’s so important to invest in building brand awareness over the long-run.” He cautions, however: “You’ll be surprised how powerful it can be to give your audience this sort of space to make your ads their own.”

In South-East Asia, Wunderman Thompson Thailand did just that in a campaign for Netflix. 2019’s Narcos The Censor's Cut [above] utilised the Streisand Effect, a phenomenon whereby an attempt to hide, remove or censor a piece of information has the unintended consequences of publicising the information more widely.

Some context: in Thailand, the censorship board is king. The challenge for Netflix was how could it market its drug-fuelled series Narcos in the face of such strict censorship?

The answer was to abide by these censorship laws to the tee, submitting the traditional trailer for the series to the Thai censorship board and letting them chop out whatever they didn’t like.

The result? A distorted trailer that raised more questions than answers, and that was so effective in its intrigue that it ended up being viewed by almost half of the country’s population.

How did such a creative idea come from such a censored place? Park Wannasiri, chief creative officer for Wunderman Thompson Thailand, explains: “The answer came directly from the brief — the biggest problem for the product was that it wouldn’t pass censorship laws, so the creative solution came directly from the restriction.” As with any other great work, then, it’s about creating a solution to a problem.

What this shows is that restrictions, perhaps counterintuitively, spark creativity.

“You always write around the problem,” says Mooge. “The film Jaws was so good because the shark didn’t work [it malfunctioned], it made the atmosphere more important which led to the classic we have today”.

Park agrees. “The best creative work comes out of limitation and struggle. Creativity began when people wanted to cook things — so they invented fire. It’s all about the struggle.”

It's a problem familiar to Paul Burke, a veteran radio advertising copywriter, who has to work with a medium which advertises brands without showing them every day.

“The worst thing to tell a creative person is, ‘do what you like and have fun with it,’” he says. “You have so much choice you end up doing nothing. The thing to remember is that in radio it doesn’t exist until you write it. As cliché as it is, you have to paint a picture with sound.”

Ultimately that is what advertising a brand without a product is all about. Painting a picture of what your brand — and by extension product — is, by leveraging the power of emotion, creativity and human nature to fill in the blanks.

As Cameron says: “All great advertising leaves a certain amount unsaid, allowing room for the audience to complete the idea or project their own desire into the message.”

The simple truth then is that you should trust your brand, preferably having built its equity through long-term brand building. If you don’t, it is likely to be time to reassess what your brand is actually about.

Because, at the end of the day, great creative always comes from overcoming problems and believing in what you're selling is worth selling, as Dickens himself wrote in David Copperfield, "Consider nothing impossible, then treat possibilities as probabilities.”

That being the case, the greatest danger isn't from some new restrictions from the outside, but rather from something much deeper within.